In my offseason study, I have run across the so-called “levels” concept multiple times and became interested with the wild claims about its effectiveness as an all-coverage beater.

When I was a freshman quarterback in spring practice when we ran a poor man’s version of the play (that wasn’t really the play at all). We ran a slant on the outside with a seam in the inside and called it “Seattle.” I liked the play because any coverage that carries the number two receiver vertically would leave a hole open for the slant to run inward (and thus make an easier throw). When I started calling plays for the JV team, I quickly put this play in. Our quarterback did not have the strongest arm, but the reality was, if he just threw it to space, the wide receiver could run to it (and sometimes under it because our quarterback just lobbed it there). The play worked to an extent because of the poor flat defender play, but the play needed help. I credit this play to helping us find one of our best wide receivers because he ran great routes right under the seam.

As you will learn, that play was not a levels concept at all, but the play’s premise formed my desire to start looking for something similar. Our “Seattle” concept was not optimal because of the slant’s angle and our inability to work the seam in the progression as anything but a run off. But because of its ability to open space so well, I knew it was worth the pursuit to create something better.

As with most of the concepts that we ran a few years ago, they were inefficient and incapable of adapting to the reality defenses presented to us.

What is the levels concept?

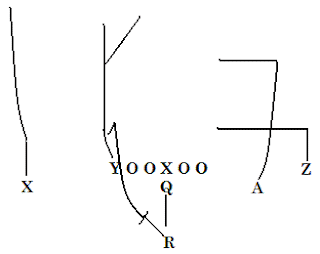

In common form from a 2x2 set, the levels concept will have a “fin” route (a five yard in route) by the number one receiver (counting outside in) and a dig route (12 yard in breaking route) by the number two receiver. In a 3x1 set (trips), the two outside receivers will both run fin routes while the number three receiver runs the deep, in breaking route.

Notice the precision of the fin route as run by Reggie Wayne in the Colts’ 2009 Divisional playoff game:

In a YouTube video, J.T. O’Sullivan gave a general description of the concept as one where “there are going to be different depths of routes all breaking in.” That means that a levels concept could consist of a dig and a shallow cross (low crossing route generally under 5 yards). Some people today might call that a “Drive” concept.

Here’s an example from the video:

Chris Brown (author of smartfootball.com) wrote an article in early 2009 in the height of Peyton Manning’s career about Manning’s favorite play: levels. Manning’s version consisted of the more common form with a fin and a dig.

Here’s how he draws it up:

And here is how Brown describes the progression:

The quarterback begins by “peeking” or getting an “alert” read of the divide route. If that route comes open or the safeties get out of position, the quarterback throws the ball on rhythm at the end of his drop for a big-play. If it is not open, he goes into his normal 1-2-3 progression.

Brown’s reference to “peeking” and “getting an ‘alert’” is the first part of the read thus making the levels concept a backside concept. That “normal 1-2-3 progression” is fin to dig to the check down from the running back.

Brown describes the premise of the play as a “a two-man high-low or vertical stretch concept, which puts the underneath defenders in a bind with a guy in front of and behind them.” Furthermore, he explains levels as a complement to the “smash”concept (hitch/fin by the number one receiver with a corner by the number two receiver).

And this idea of the levels concept being a backside concept opens the door to increasing the concept’s versatility. We can now treat the frontside as a blank canvas available as a place for our best concept to attack any given opponent. Meanwhile, we keep a comfortable, all-purpose concept on the backside that comes into the quarterback’s vision.

To recap the concept in its most basic form: the levels concept is a backside concept that puts an underneath, zone defender in a vertical bind by using routes that break coming right at him with one above him and one below him. Now knowing the premise is fine, but as I have learned, it is just as essential to understand the precise situations in which you want to call this play as it is to know the details of the play.

Why run levels?

Levels is first and foremost a two-high safety beater. Paired with smash, the concept can be deadly against Cover 2. Smash is a concept that vertically stretches the cornerback while levels, as stated prior by Brown, vertically (and perhaps horizontally) stretches an inside linebacker. Smash attacks the hole created on the sideline by the high safety and the low corner with the corner route. Levels attacks the middle of the field in between the two high safeties and underneath defenders. Coach Barry Hoover even states on his blog that he “believe[s] Levels is a higher percentage play vs. Cover 2 than Smash, making it well-suited for teams that want to control the ball with the forward pass.” This may be true, but having both ensures you can defeat different techniques within Cover 2 that a defense will present.

Here’s a drawing of levels as a frontside concept against Cover 2:

As shown in the drawing, when the Sam/Nickel linebacker walls (runs vertically with) the number two receiver’s vertical stem. Because I am treating the concept as a frontside concept here, the primary goal is to get the ball to the fin route because the dig takes longer to develop. So, the quarterback must read the Sam and if he takes the vertical stem at all, then the fin can attack that open space between the outside leveraged cornerback and the Sam’s departure.

However, as mentioned by O’Sullivan in that same YouTube video mentioned earlier, Cover 2 Man (man coverage underneath two safeties each responsible for a half of the field) is a horrible coverage to run levels into because the man defenders play with inside leverage and help from safeties over the top. So we must return to Manning for a solution.

O’Sullivan explained that Manning would just signal an out route (10 yard out breaking route) to the dig runner whenever they got Cover 2 Man. Now a simple tag can protect the play against a coverage that would have otherwise destroyed the play.

Here’s a drawing of their solution:

That open space is abundant, and this simple tag begins to show how the concept is so adept at being able to morph into the space the defense presents to the offense.

How to adapt for Cover 1

But there are even more ways to expand the play to create a versatile attack from this one concept. For example, the out route tag is great against Cover 2 Man because it breaks away from the half field safety in a way that doesn’t allow the safety to undercut the route. However, against Cover 1, there is no need to run an out route because that half field safety does not exist. In Cover 1, the safety will be playing in the middle of the field. So in order to maximize the gainable yardage, a corner route by the number two receiver is better. The corner also is a better route than the out route for beating Cover 1 because of the man defender’s leverage.

Here’s a drawing:

In Cover 1, the inside defenders are most likely going to play with outside leverage in order to maximize the help available to them inside from the middle of the field safety. Trying to run a route that breaks into that leverage is not optimal, so the corner route’s angle will still attack the outside space but the higher angle will help the receiver run away from the defender leading him to a splash down zone of about 22 yards (Adapt or Die: Maddox, 59).

Before we end…

As you have learned, the play is versatile, but the truth is that we have not even touched on the magnitude of its versatility against by looking at more route breaks to defeat other coverages and using different progressions to amplify the play’s effectiveness. So far, we know that the play is usually a backside concept that has two or three in breaking routes at different levels. To combat man coverages, an outside breaking route (an out or a corner) should be used in place of the dig. Now these tags create new concepts, but that’s perfectly okay. Our goal is to create concepts that only make sense when seen together.

By creating a concept that can adapt for different defensive techniques by morphing into new concepts built around the same starting point, your playbook will grow with the purpose of each play concept protecting another.

And in a world dominated by effective efficiency such as high school football, this ability is a high value commodity worth pursuing.

In Part 2, I will dive deeper into the idea about using one concept to build others by further exploring the intricacies of the dig route and how a full field read elevates the concept to new levels.

If you liked this article, please subscribe to make sure you get notified when Part 2 is released!